May 10, 2017: DHCF Testimony- FY 2018 Budget Hearing

Introduction

Good morning Chairman Vincent Gray and members of the Committee on Health. I am Wayne Turnage, Director of the Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) and it is my pleasure today to report on Mayor Muriel Bowser’s FY2018 budget entitled “DC Values in Action: A Roadmap to Inclusive Prosperity.” I have submitted written testimony for the record and will rely upon the presentation you have in your possession for my comments.

The Mayor’s budget is constructed to provide targeted investments in areas that make the District more affordable and safe while alleviating the tax burden for its middle class residents. In the development of her FY2018 budget, Mayor Bowser executed a public engagement process that included three budget forums across the District in which residents could speak to the priorities they believe the administration should pursue in the formation of the proposed FY2018 budget. These forums were supplemented by meetings with councilmembers and key stakeholder groups to solicit their input in the budget development process. As a part of this effort, DHCF regularly met with our Medical Care Advisory Committee, in part, to hear the members’ views on important Medicaid and Alliance budget issues.

Also, as in previous years, the Mayor challenged agency directors to target underspending, existing staff vacancies, and program inefficiencies as a means of identifying funds that might be redirected to a higher use. This effort did not include the blunt instrument of across the board reductions but rather required agency directors to strategically assess their operations for areas of possible adjustment.

As you are aware, the budget for the Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) -- at more than $3 billion -- is a critical component of the Mayor’s budget. With an excess of $700 million in budgeted local funds, DHCF accounts for a significant share of the city’s portfolio of local spending, second only to the District of Columbia public schools. Accordingly, DHCF can play a vital role in identifying cost savings and thereby provide relief from some of the District’s fiscal pressures.

However, as we annually note, the nature and structure of DHCF’s budget introduce a number of complications that must be considered in any process designed to generate savings for possible reallocation to other priorities. Specifically, though we annually spend over $3 billion in combined federal and local dollars, fully 96 percent of this spending can be traced to Medicaid provider payments which are directly influenced by a variety of factors including beneficiary utilization levels, the scope of authorized benefits, and provider reimbursement rates. The remaining four percent of the budget funds personnel costs, contractual services, and other administrative costs that are central to the operation of our programs. As with provider payments, each local dollar, including those spent on FTEs, are matched with between 45 and 90 percent of federal funds.

In practical terms, this underlying financing scheme means that major savings in Medicaid -- and to a lesser degree the much smaller Alliance program -- can only be realized through either reductions in participant eligibility levels, policy changes that narrow the scope of recipient benefits, or decreases in provider reimbursement rates. If these options are not considered, smaller savings opportunities can sometimes be achieved through the capture of administrative efficiencies and the opportunistic pursuit of any one-time savings actions that can be identified.

I am pleased to report that as we stand in the shadows of the resurgent national health care reform efforts that would undermine the coverage goals of the Affordable Care Act, Mayor Bowser’s FY2018 budget fully embraces the District’s long standing commitment to preserving eligibility levels for both the Medicaid and Alliance programs – thresholds which are among the highest in the United States. Further, as in past years, the Mayor’s budget protects the full range of preventive, primary, acute, and specialty health care services funded through these two programs.

As an alternative to lowering Medicaid and Alliance eligibility levels or reducing the scope of benefits, the Mayor has proposed cuts to DHCF’s budget through actions that:

Smartly shift funding for certain provider payments to another fund source;

Mine funds from previously budgeted local dollars that were designed to draw down federal funds which are no longer needed;

Capture anticipated savings from stepped up agency enforcement efforts; and

Realize savings due to the timing of certain program changes.

These proposed actions produce $25.4 million in savings for FY2018 and, when netted against other increases and transfers authorized in the Mayor’s budget, resulted in $9.8 million in local fund reductions without any changes to program eligibility benefit levels. This is a significant accomplishment.

My remarks today initially focus on the three major issues that shaped our budget development for FY2018. First, I discuss how DHCF’s FY2018 budget was formulated taking into account the FY2017 authorized budget and the impact of the FY2018 Current Services Funding Level (CSFL). Second, I offer some detail on several of the key savings strategies authorized by Mayor Bowser to generate $25.4 million in gross local fund savings. Third, I briefly report on some of the more significant mandatory and optional allocations for certain Medicaid services, along with a report on the Mayor’s six-year capital funding plan for the United Medical Center Not-For-Profit Hospital Corporation (UMC). Finally, I close out my testimony with a report on the changing enrollment patterns in the Medicaid and Alliance program, the implications this holds for the cost these programs, and, given the reprisal of national health care reform, a brief review of the potential impact on the District.

DHCF's Budget Development Process

Mr. Chairman, as you are aware, budget development is a highly structured process involving multiple steps and iterative interactions between the agency and the Mayor’s budget team. This portion of my testimony outlines the steps that were implemented to construct the Mayor’s budget for DHCF.

Budget Development.

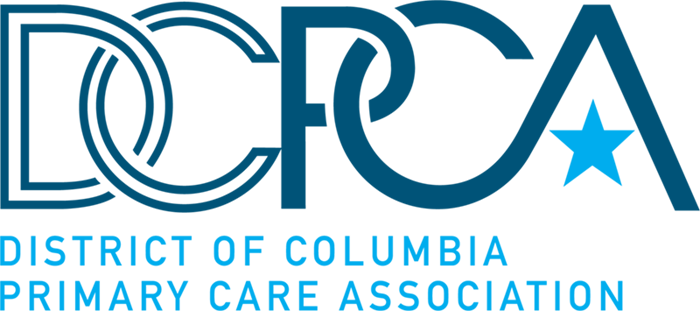

As shown by the illustration below, the Mayor relied upon DHCF’s current year’s budget of $705 million to set the base funding level in FY2017. Next, this budget amount was inflated by employee salaries and fringe benefits, anticipated growth in Medicaid direct services, and changes in the Consumer Price Index. This produced an estimate of our CSFL which, in this case, is defined as the cost of providing the same Medicaid and Alliance services in FY2018 that were funded in FY2017. This increased the local fund budget for FY2018 to $722.4 million.

The increase in the CSFL from the FY2017 base budget was a modest 2.3 percent or $16.8 million. As anticipated, the majority of this increase -- over 90 percent -- reflected the additional projected cost of funding more than $15.3 million in Medicaid direct care services. This represents the combined effect of the anticipated growth in beneficiary enrollment, utilization, and heath care inflation, pushing the FY2018 proposed local budget to $722.4 million.

Finally, through a complex series of increases and offsetting reductions, DHCF’s local fund budget was, as noted earlier, reduced by a net of $9.8 million. At a high level, this amount is the net effect of four adjustments: 1) $16.9 million in local fund increases for contracts, personnel cost that were in excess of the CSFL adjustments, and forecasted increases among Fee-For-Service provider types; 2) a $25.4 million reduction DHCF was asked to assume mostly in provider payments; 3) a $50,000 enhancement to support the local cost of a staff person to set up the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE); and 4) a transfer of $1.4 million in local funds to the District of Columbia Office on Aging (DCOA) to support the cost of the Aging and Disability Resource Center (ADRC). This results in a $712.7 million proposed local budget for the agency – 1 percent higher than the FY2017 base budget.

DHCF Proposed Savings Initiatives

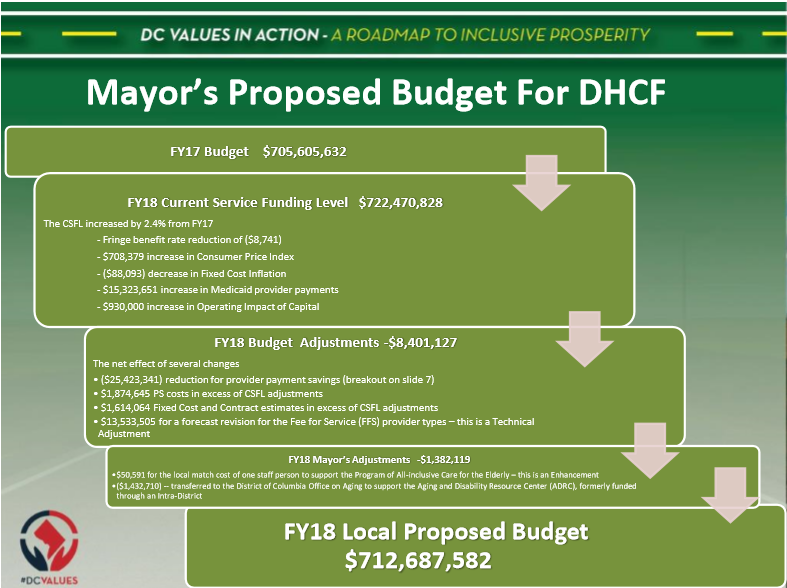

As noted early, the Mayor has authorized five major budget actions which generated $25.4 million in initial reductions to DHCF proposed budget for FY2018. In terms of order of magnitude, the two most significant actions were $14.4 million in local funding that was targeted to draw an additional $33.7 million in federal funding for the Disproportionate Share Hospital Fund (DSH) program. This and the other budget actions are described in the illustration shown below.

Meaning of DSH Reduction.

It is especially critical to note that this $14.4 million reduction does not represent a cut to the hospitals that participate in the DSH program. The Mayor’s budget includes sufficient local funds to draw down the full amount of DSH funding that hospitals were projected to need based on the DSH survey completed in FY2016. This $14.4 million reduction represents the difference between the amounts that hospitals are eligible to receive (called the federal DSH limit) and the amount we projected they would be able to absorb based on their projected uncompensated care costs (called the hospital specific DSH limit), which are suppressed due to the District’s high health insurance coverage levels.

Nursing Home Reduction.

The next largest proposed savings is a $6.9 million reduction to nursing facilities. Currently DHCF sets rates for nursing facilities based on their actual costs. These rates are rebased every three years using the nursing facilities audited cost reports. As a refinement, the rates are further adjusted every six months for patient acuity levels.

Under current State Plan rules, nursing homes are allowed to appeal the audit results to the Office of Administrative Hearings. While this protects the appeals rights of the industry, it significantly delays the rate setting process because DHCF must use final audited cost reports to set the reimbursement ceilings that are central to the methodology.

As an example, DHCF is still waiting for the appeals process to play itself out for the FY 2013 cost reports which impact nursing home rates for FY2015, FY2016, and FY2017. This means, of course, that nursing facilities are getting paid on rates that were set based on audits of FY2010 cost reports, and thus, to address this lag, we must make interim payments based on estimated FY2013 rates, inflated forward.

To resolve this problem, we developed a joint agreement with the provider community to build a new rate reimbursement process, marrying the best of what we can extract from the existing system with new methods that improve the entire process. This new rate methodology will be a prospective payment system, eliminating the need for a retrospective and protracted “true-up” process.

The original plan was to have this new rate methodology approved and ready for the FY2018 budget starting October 1, 2017. Due to difficulties in gathering data from various sources during the initial development stage, it was decided that this new methodology would be made effective January 1, 2018. This creates three months of savings.

Also, as part of the rate development process, we initially built in payments to support an incentive program in FY2018. Subsequently, DHCF and the provider group decided that FY2018 would be the period for data collection and analysis as a precursor to the implementation of the pay-for-performance plan. Hence, the program will not start until FY2019, thus creating additional savings in FY2018. Combined, these two factors allowed DHCF to reduce the local fund share of the nursing facilities budget by $6.9 million.

In significantly smaller amounts, the proposed savings plan indicates our plans to generate $1.6 million by eliminating Medicaid eligibility for persons who are no longer District residents but still enrolled in DC Medicaid and another $1.6 million through the use of surplus dollars from the agency’s non-lapsing Healthy DC fund to cover expenses previously paid for with local funds.

Proposed Funding Levels For Critical Medicaid Mandatory and Optional Benefits

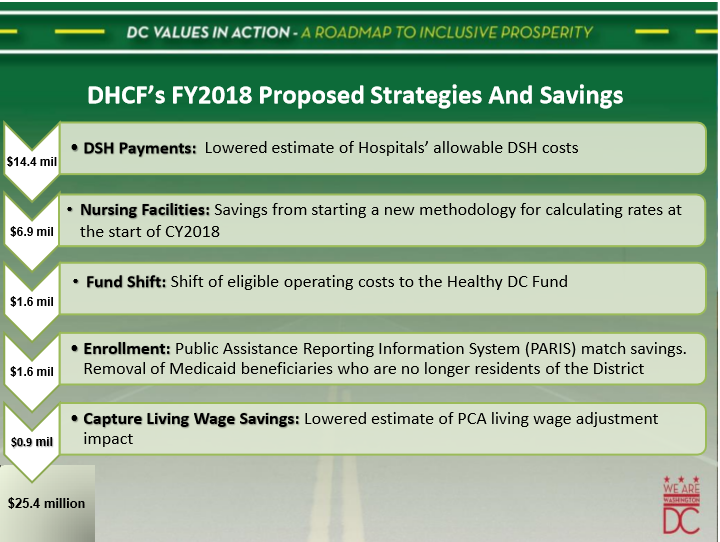

As a condition of participation in the Medicaid program, the District is required to provide a certain range of benefits, referred to as mandatory services, while having the discretion to provide certain optional benefits. The proposed funding, which sets FY2018 levels for the mandatory services, are shown in the table on page 10.

The largest funding amounts are proposed for the high-end hospital inpatient acute care services and nursing home care. Additionally, the Mayor’s budget makes significant allocations for primary clinic services through the Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC), hospital outpatient and emergency care, and primary physician care services provided outside of the FQHC environment.

It is important to note that for hospital inpatient and outpatient services, the amounts in the Mayor’s budget for FY2018 are significantly less than the amounts budgeted in FY2017.

These funding levels reflect payments that are designed to cover 86 percent of the hospital’s cost for delivering inpatient care to Medicaid beneficiaries and 77 percent on the outpatient side. This translates into amounts which are less than the reported expenditure levels in FY2016 and the budgeted figures for FY2017.

These differences are explained by the fact that the proposed funding for FY2018 does not include the higher payment levels that are funded by hospital provider taxes. However, the District of Columbia Hospital Association has indicated that it will request that this assessment be established by the Council for FY2018 which will raise the funding amounts for inpatient and outpatient care to levels that equal or exceed the amounts spent in FY2016 and budgeted in FY2017.

For optional Medicaid services, the most significant allocation in the Mayor’s budget is the managed care payments for our three full-risk health plans. The District funds these payments through the use of the actuarially sound rates on which the health plans are anchored, and in FY2018 the Mayor is proposing over $1.2 billion to support this program making it the largest expenditure in DHCF’s budget.

United Medical Center Capital Budget.

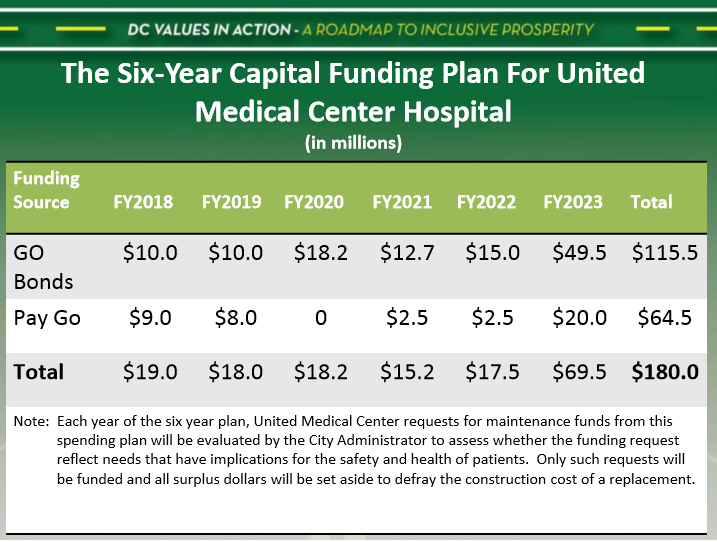

To address both the deferred maintenance needs for the UMC and reserve funds to support the construction of a new hospital, the Mayor has allocated $180 million for these projects in her six-year Capital Budget Plan. As shown below, the allocations for the first five years of the plan range from a low of $15.2 million to a high of $69.5 million. The general goal is to use most of the funds in the early years of the plan to fund those needs which must be addressed to maintain patient health and safety standards.

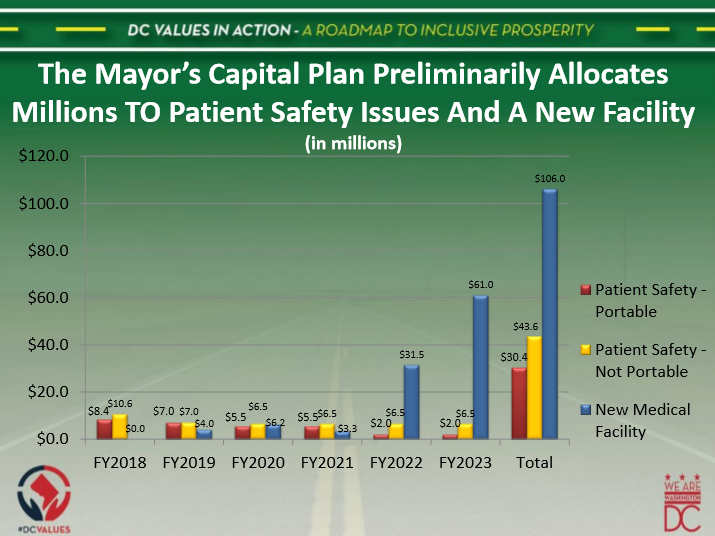

Increasingly, as the end of the six-year period approaches, a greater share of the allocated capital dollars will be set aside to assist with the construction of a new hospital. The graphic shown below outlines this plan, demonstrating the anticipated funding for maintenance projects that are portable to a new facility versus those that cannot be transferred. In FY2018, the entire allocation of $19 million is set aside for pressing needs. However, by the end of the six-year time period, the Mayor is projecting that $106 million will have been made available to defray the cost of a new hospital, with the remainder being spent on both portable patient safety projects ($30.4 million) and the balance ($43.6 million) on similar projects, the future value of which will be lost, unfortunately, when UMC is razed.

These allocations reflect general plans which are subject to revisions on a year-to-year basis. Each year, UMC officials are required to submit a proposed capital spending plan to the City Administrator to be considered for the Mayor’s budget. In developing this plan, UMC’s operator, Veritas, aims to balance the capital needs of the hospital with the competing priority to reserve funds in support of the goal to construct a new facility for the residents of Wards 7 and 8. Subsequently, the Mayor’s budget team, under the direction of the City Administrator, subjects UMC’s capital request to significant scrutiny. As a part of this process, any of the resources planned for capital projects which are not approved in a given year of the six year plan will be diverted and reserved to pay for part of the cost of new hospital construction.

Medicaid and Alliance Spending Patterns: Trends and Future Challenges

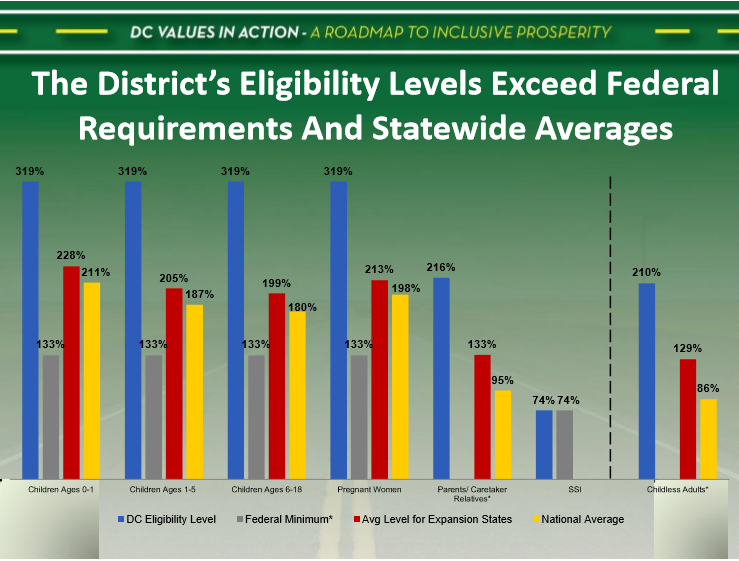

Mr. Chairman, this portion of my testimony focuses on overall enrollment levels in the Medicaid and Alliance program. With the series of eligibility changes approved by the DC Council over the past six years, the District of Columbia has emerged as a national leader in providing access to publicly-sponsored health care for persons with low incomes. Due to this commitment to coverage, national data show that for nearly every beneficiary category, the District has established significantly higher eligibility levels than the average thresholds observed for other states.

Clearly demonstrated in the graphic on page 14 are the substantially higher eligibility levels for children and adults. Notably, for children of all age groups, Medicaid eligibility levels in the District are set at 319 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). As reported in the figure, this exceeds the federal minimum requirement, the national average for all States, and the average level for jurisdictions that have expanded their Medicaid programs.

For adults, the differences reported are even more striking. While the District extends eligibility for parents and childless adults to 216 percent and 210 percent of the FPL respectively, the average for other expansion states is 133 percent. Among these states, the highest childless adult eligibility rate is 138 percent of FPL. Further, no individual State provides access to State Plan Medicaid-funded health care to families with incomes that exceed 148 percent of FPL.

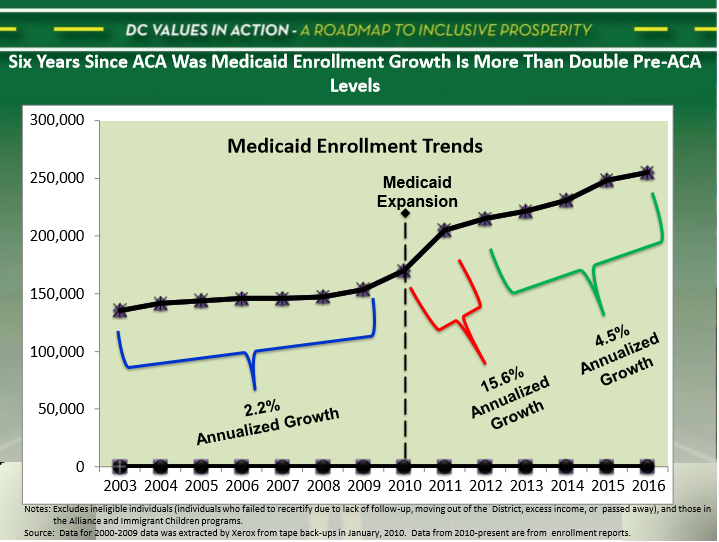

The impact of the District’s more aggressive policies for the Medicaid program can be seen in the enrollment trends for program beneficiaries that quickly spiked following the implementation of expansion policies in 2010. Prior to the adoption of these policies, the enrollment growth in Medicaid averaged 2.2 percent annually (see graphic on page 15).

In the first year after expansion, the growth rate jumped to more than 15 percent. While this increase moderated over the time period from 2012 through 2015, the annualized growth rate for this period of 4.5 percent is still more than twice the level observed in the years prior to expansion. This suggests, of course, that the expansion population is continuing to grow at a faster rate that experienced by the legacy Medicaid populations.

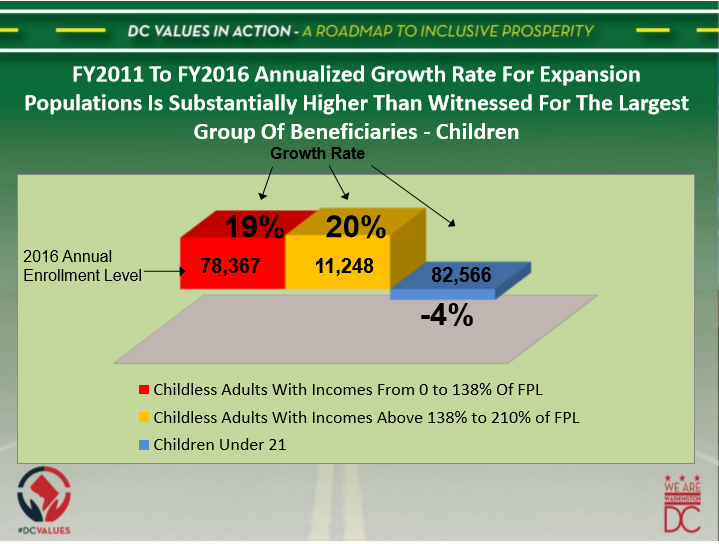

As stated earlier, in addition the childless adult population with incomes from 0 to 138 percent of FPL, the District is the only Medicaid program that provides State Plan Medicaid coverage for the childless adult population with incomes above 138 percent to 210 percent of federal poverty. In other expansion states, this population is required to secure health insurance from the exchange, using the income-based federal subsidies to offset the cost of the premiums charged by private plans.

Not only does the District cover the full health insurance cost for this this group, but the city must contend with the rapid rate at which this population is growing. Specifically, in FY2016, 11,248 Medicaid recipients enrolled in the program under this coverage. This represented a 20 percent annualized growth rate from FY2011. By comparison, enrollment growth for children over this same time period was a negative 4 percent, while the rate for the legacy expansion population was 19 percent (see graphic on page 16).

In terms of cost, the childless adult group with incomes over 138 percent of FPL is significantly more expensive to care for due to the disproportionate representation of persons among this population with chronic illnesses. These differences are reflected in FY2017 managed care rates as DHCF is currently paying our three full-risk MCOs premiums of $519.80 per-member, per-month for this sub-group of adult Medicaid beneficiaries without children. By comparison, the health plans are receiving $455.65 per-member, per-month for all other adults, and only $223.60 for children.

Because this population has historically been the most expensive non-elderly population to serve in the District’s Medicaid program, the double-digit growth rates have significant cost implications. Notably, in FY2018, we anticipate spending more than $100.4 million in total funds to pay the coverage cost for these beneficiaries. Moreover, when we consider the entire childless adult population -- those with incomes from 0 to 210 percent of FPL -- the total cost will be more than $623 million for an estimated 90,000 recipients.

Alliance Program.

Mr. Chairman, the next topic of my testimony focuses on the Alliance program. In a market that is closed to all private insurance plans that do not participate on the federal exchange, the Alliance program is the only link to coverage for District residents who do not presently enjoy United States citizenship or are legal immigrant residents within the five-year period of their arrival in the U.S.

Since its establishment in 2001, the DC Healthcare Alliance has played an integral role in improving healthcare access for uninsured District residents. Originally funded to provide a comprehensive network of integrated health care services to otherwise uninsured low-income District residents with incomes under 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), the Alliance was converted to a managed care program in 2006 to ensure a more financially sustainable means of providing improved access to health services while enhancing care coordination and better health outcomes for District residents who were previously uninsured and served primarily by DC General.

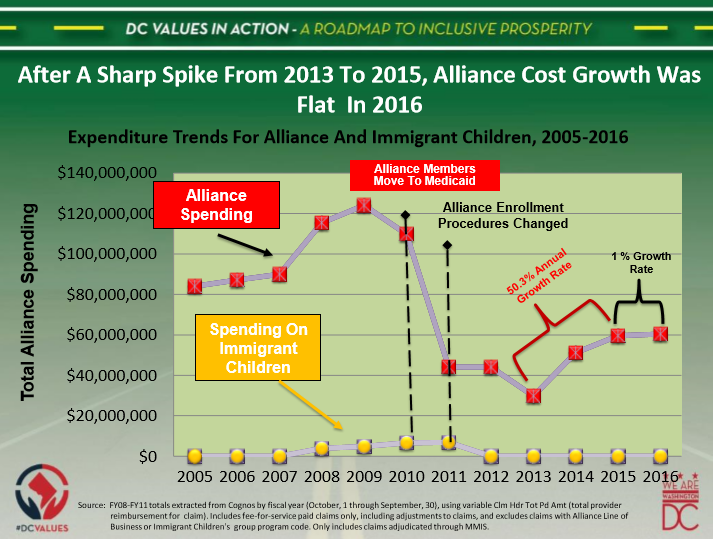

Since that time, the Alliance program has played a key role in promoting health coverage and improved access to a broad array of health care services among District residents. In FY16, the District spent $60 million to provide coverage for 15,000 Alliance enrollees. However, it is well documented that District leaders have wrestled with competing tensions throughout the Alliance’s history – more specifically, balancing the goal of preserving access to care against financial viability and the real risk of nonresident enrollment given the District’s proximity to other states with less generous coverage. For this and other reasons, the structure and eligibility criteria for the Alliance program have evolved over the years.

In 2006, the Alliance program began offering coverage through the same privately run managed care plans as Medicaid beneficiaries. The managed care plans are held to the same network adequacy standards, quality metrics, and financial stability requirements as in their Medicaid contracts.

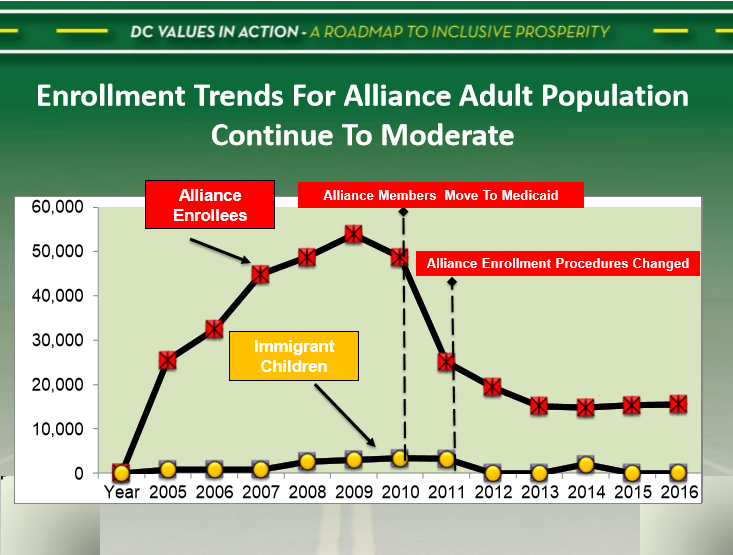

The enrollment in Alliance has fluctuated significantly with the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, as the District availed itself of the opportunity to expand Medicaid to previously ineligible low-income childless adults who were, at the time, covered under the Alliance program. In a two-step process, the District expanded Medicaid to cover adults up to 200 percent of FPL. As many Alliance enrollees gradually transitioned to Medicaid, Alliance enrollment declined to just those adults who remained ineligible for Medicaid — mostly undocumented immigrants and legal immigrants within their first five years of residence. Thus by the end of FY2011, Alliance enrollment had fallen by 59 percent to 23,511 (see below)

Sources: Excludes ineligible individuals – persons who failed to recertify due to lack of follow-up, moving out of the District, or had excess income, or passed away. Data for 2000-2009 data was extracted by ACS from tape back-ups in January, 2010. Data from 2010-forward are from enrollment reports.

However, even after this transition, the Alliance program faced financial pressures that threatened its future — pressures that were believed to be associated, in part, with a growing number of enrollments in the program by non-District residents. In response, on October, 2011, DHCF implemented a new eligibility process requiring face-to-face interviews to determine eligibility and requiring beneficiaries to recertify eligibility every six months. Alliance enrollment declined in two successive years following the FY2011 implementation of the six (6) month face-to-face recertification policy. Since that time, average monthly enrollment has remained steady at about 15,000 individuals.

Notwithstanding this stabilization of enrollments, the cost increases for the program for several years were unabated. Specifically, in the second year following the change in recertification policies, the cost of the program grew by 50 percent from FY2013 to FY2015 (see below). And now with enrollments averaging 15,000 members per month, the program’s annual cost is right around $60 million – nearly all local funds. The Mayor fully funds this cost through the managed care rates which are included in her proposed budget for FY2018.

Reemergence of Health Care Reform Efforts.

On May 4, 2017, The U.S. House of Representatives secured, by a narrow margin, the necessary votes to pass a bill that would substantially alter the Affordable Care Act. With votes along mostly partisan lines, the House bill, similar to the early version that failed, would radically reshape Medicaid, ending the program’s most sacred feature – the open-ended entitlement for persons with low-incomes.

Replacing the entitlement, the bill proposes that states be given the option to receive a capped allotment of federal money for each beneficiary, or, as an alternative, a block grant, unhinged from the many federal requirements governing the current Medicaid program.

Largely unchanged from the early bill are the changes proposed for Medicaid expansion. As we noted at that time and what remains true now, this proposal has the potential to grow the non-federal share of the program unless, over time, states roll back eligibility levels, reduce benefits, or lower provider payments especially in years where federal inflation adjustments are insufficient to cover actual utilization and provider payment rate increases.

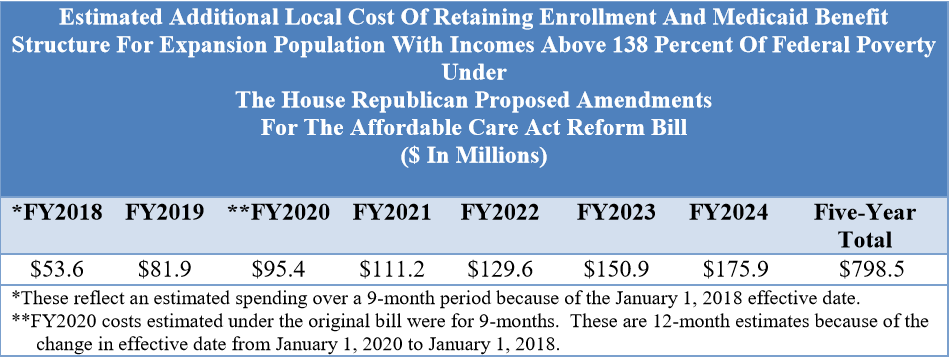

The most immediate impact of the House bill on the District would be generated by the provision that requires an earlier sunset of the particular Medicaid expansion policy for persons with incomes above 138 percent of federal poverty. If this bill passes out of the Senate with this provision intact, after January 1, 2018, no state would receive any federal match for this group. The expectation is that these persons would use federal tax credits -- which are reduced relative to the amounts provided for in the Affordable Care Act -- to purchase health care insurance off of the individual market.

In the District, as noted earlier, we define this population as childless adults with incomes from 138 percent to 210 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). There are now, roughly 15,000 persons in this category and we updated the estimates to reflect the District’s likely exposure beginning in FY2018 should the House bill pass.

As shown below, the changes will add 9 months of local cost in FY2018, creating a $53.6 million exposure for the District if the city opted to continue coverage for this population. Looking out over a seven-year period, the anticipated cost of covering only this population would reach nearly $798 million. When all the existing Medicaid provisions of the bill are considered, the cost to the District in the next five years could fall within the range of $1.8 to over $4.1 billion.

Conclusion

In closing, Mr. Chairman, the Mayor’s budget for DHCF is only slightly higher from the levels budgeted in FY2017. Nonetheless, this proposed budget was sufficient to fully fund the higher than national average Medicaid insurance coverage levels which have become a hallmark symbol of the District’s commitment to provide comprehensive coverage to persons with low income.

In support of these high coverage rates for both Medicaid and Alliance, the Mayor has proposed the necessary funding to offer beneficiaries in these programs a full array of health care benefits that ensures access to preventative, primary, acute, and specialty care services. Therefore, it is incumbent upon DHCF to work with the health care provider community to warrant a delivery system that minimizes waste and inappropriate utilization, while constructing incentives to encourage providers to deliver the best possible value to the District per health care dollar spent.

And as we focus on these laudable goals moving towards FY2018, my staff and I will continue to play close attention to the national efforts to reform healthcare in Congress. With the reemergence of the House bill, this remains the greatest threat to the future viability of the District’s comprehensive public health insurance program.

This concludes my remarks and I, along with members of my management team, are happy to address your questions and those of the other members of the committee.